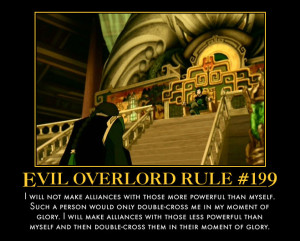

“Evil Overlord Rule 199†by Ares Johnson

Oh, once there was a wicked, wicked man

And Haman was his name sir,

He would have murdered all the Jews,

Though they were not to blame sir

Oh today, we’ll merry, merry be

Oh today, we’ll merry, merry be

Oh today, we’ll merry, merry be

And nosh some hamantashen.

I posted a link to this classic children’s Purim song, earlier this week.

The first challenging thought that forces itself on me: What makes us think that Haman was “wicked”? I’ve written before about Haman’s humanity. There, but the for the grace of God…

The stories we tell affect how we think about the world. And our portrayal of Haman as nothing more than a “wicked, wicked man,” and rejoicing in his death, makes us no better than he. God himself takes “no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but rather that they turn from their ways and live” (Ezekiel 33:11). At a very basic ethical level, we ought not to rejoice in our enemies’ misfortune.

But moreover, the characters we focus on, we tend to become more like them. Jesse Walker, in The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory, quotes Richard Hofstadter:

This enemy seems to be on many counts a projection of the self… The Ku Klux Klan imitated Catholicism to the point of donning priestly vestments, developing an elaborate ritual and an equally elaborate hierarchy. The John Birch Society emulates Communist cells and quasi-secret operation through “front†groups, and preaches a ruthless prosecution of the ideological war along lines very similar to those it finds in the Communist enemy. Spokesmen of the various Christian anti-Communist “crusades†openly express their admiration for the dedication, discipline, and strategic ingenuity the Communist cause calls forth.

And then Walker spends over 400 pages demonstrating that this applies to all of us, whether we’re on the fringe or in the so-called mainstream.

If it’s odd to see Communists and McCarthyists concerned about conformity, it should be odder still to see the professed enemies of totalitarianism endorsing authoritarian measures. Instead it is common, and it has been for as long as totalitarianism has existed.

We become the people we hate, because those people are us.

In the words of psychoanalyst Albert Mason, in the documentary Beyond Right and Wrong: Stories of Justice and Forgiveness:

What allows one group of human beings to annihilate another group is if they find a way of dehumanizing them. Now, you do that by taking aspects of yourself that you hate, that you feel are bad, despicable, and you want to disown them. And you put them into the victim. Then the victim is experienced as a disease or a scourge and can be annihilated.

For forgiveness to occur, the process must be put into reverse, where the victim has to see the perpetrator as not all bad or evil, and this can occur if they see that the perpetrator shows genuine remorse, guilt, and takes real steps to repair or rebuild the damage they’ve done.

Haman certainly made this error. And we, like Esther, make the same error, and thereby scar our own souls. We dump the worst that humanity represents into this one character and reason that, if only he were another sort of man, then all would have been well. I’d like to propose an alternative narrative, that Haman’s problem was not that he was wicked, but that he was powerful.

We forget, for example, that King Achashverosh (aka Xerxes) was informed of, and approved of, all that Haman had planned. If Haman’s wickedness is the fundamental problem, then genocide must be perfectly fine, as long as it’s not Jewish genocide. Or that if Jewish identity really had threatened Achashverosh’s lordship, then it would have been perfectly reasonable for him to have had them exterminated. I have trouble buying into that.

Lord Acton nailed it: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority, still more when you superadd the tendency or the certainty of corruption by authority.”

Haman’s downfall becomes merely another sad story of paranoia, influence, sex, and status, of the intolerant powerful’s fear of those they don’t understand and can’t respect, of their inability to live in peaceful civil society with others who believe differently than they do.

This is a story that applies directly to our modern politics, today.

And so maybe we should focus on our own attitudes and uses of power, rather than on our hate of a “wicked, wicked man.”

Excellent article, Tim! I think that you are right that what ought to separate us from our enemies is our willingness to not treat them as they’ve treated us. That said, I think there are some things about the book of Esther itself as well as some streams of rabbinic thought on Purim that are worth mentioning.

1. The Bavli, in Masechet Chullin 130b includes the following: “From where in the Torah can [a reference to] Esther be found? ‘And I will conceal my face on that day [Deuteronomy 31:18].'” The word for conceal, ×ַסְתִּיר, is similar to ×ֶסְתֵּר. There are a few different ways to read this. The first is that it is just an explanation as to why God’s name isn’t mentioned in Esther. There’s a very “spiritualized” reading that Godself is hidden within Esther herself (I kinda like that, in its own way :-). But, per your points Tim, there is something about what goes on in the book of Esther that is an example of God’s departure from the scene. so, while our tradition certainly praises Esther and Mordecai, and justifies much of the story. There is still a sense in which our Sages see the drama of what happened as a reflection of the “hiddenness” of God. Ambivalent, much? I think this deals with the reality that Esther is the only book without God, in some sense. It is therefore worth suggesting that the joy and celebration are tempered by the fact that there’s no land of Israel, no Torah, and our protagonist heroes are Esther (named after Ishtar?) and Mordecai (named after Marduk?). It is a victory, but one tempered greatly by less-than-ideal components.

2. In b.Megillah 7b, we read: “Rabba said: It is the duty of a man to intoxicate himself [with wine] on Purim until he cannot tell the difference between cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordecai’. Rabba and R. Zera joined together in a Purim feast. They became mellow, and Rabba arose and cut R. Zera's throat. On the next day [Rabba] prayed for mercy on his behalf and revived [R. Zera]. Next year he said, come and we will have the Purim feast together. He replied: A miracle does not take place on every occasion.”

This is maybe the most hilarious gemara…Ever. That said, I think you can read deeper meaning into the discussion. Something about the very act of celebrating Purim does violence to us, from which we may not always recover. Should we really celebrate that much? If we do celebrate this day of destruction of our enemies, we may need a miracle to recover. Maybe our joy should be a little tempered.

So…in the spirit of these readings, in the spirit of this day of fasting, and in the spirit of the coming Pesach where at the seder we’ll diminish our cups in remembrance of those lost on our way to freedom I suggest it is worth celebrating victories (even when not total) always tempered with the willingness to be ambivalent about the circumstances. Even rejecting the “costs” we once accepted in the past. Just like you reminded us!

Wonderful comments, Rabbi Ben. And thank you for your kind words.

This year, it has deeply struck me how conflicted the story of Esther is, how full of opposites. A fitting prelude to Pesach.

-TimK