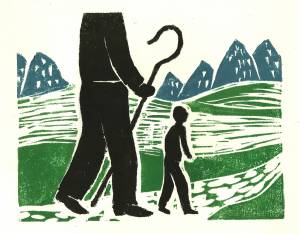

“Walking with God”

Photo © 2012 Rick & Brenda Beerhorst CC BY 2.0

Click here for the original image.

A couple weeks I posted a long, theological piece called “Running for God,” which I had expected would inspire controversy and boredom (though not necessarily in that order). Instead, I got some encouraging comments on it.

I had originally written the piece as my final essay for a Foundation theology course at MJTI that I had taken. But in the original essay, after I disagreed with Rick Warren, pushed for a physical salvation in the here-and-now (not just a spiritual one in the forever-after), stated that what we do in this life matters, and quoted Rabbi Jonathan Sacks on human distress and poverty, I went on to discuss faith and works in the context of postmissionary Messianic Judaism.

I now present that discussion.

This brings me to a key debate within Christian circles, a debate that Christians have largely missed the boat on, the issue of faith and works.

When I was a young man, my father pastored a church at 666 Walpole Street. After some years, some denominational officers called him into a meeting, along with church board members, where they questioned his theology regarding salvation. A Christian, once saved, can he ever do anything that will cost him his salvation? Are we saved by faith? Or are we saved by our works? It’s a classic controversy amongst Christian theologians. One side, the Calvinist view, says that once we believe in Jesus Christ, we’re saved for eternity, regardless of what we do afterward. The other side, the Wesleyan view, says that our salvation depends on whether we follow God’s commands; if we ignore him, fail to love him and fail to show love toward our fellow humans, we cannot be saved, no matter what we claim to believe.

So the challenge was: if someone believes in Christ to salvation, can he later renounce that salvation by turning to a life of sin? Dad had no good answer for this challenge, because how can we see into the heart of another person? To God he stands or falls.

But these officers were seeking Dad’s dismissal, and they got it. The dispute split the church, as such disputes almost always do. And with an ironic but sorrowful twist: The church and denomination were taking the Wesleyan position, that how a man lives matters more than the belief he professes. Then the real scandal came, that the officer spearheading the charge was plagued by a conflict of interest. He apparently wanted the church for himself. The false charges were proved ridiculous. More firings were no doubt executed. By then, the damage had been done. It was too late to save the church.

So what does this story teach us about faith and works? At the time, I wrestled with grief and anger. I did feel that this life mattered, because the travesty that had been done to my church and my family had no excuse. But at the same time, I had always believed that we live for spiritual salvation, based on our faith, regardless of our faithfulness. I wanted so much to resolve this conflict, and I approached my manager at work, who allowed me an afternoon off, so I could sit under a tree and pray and study. Looking back, I see an immature, young man desperately seeking answers. But even in my immaturity, I think I got the gist of the scriptures’ message:

Faith and works is the flip side of the salvation coin.

Note how I now always say, “faith and works,” like “spaghetti and meatballs.” It’s a singular noun, a whole thing. It’s not, as many Christians believe, a dichotomy, the spiritual versus the physical, as though they can be separated somehow. “Faith” and “faithfulness” are the same thing, even represented by the same word in the Biblical languages. You can’t have one without the other. Asking whether we’re saved by “faith” or by “works,” that’s like asking whether you’re still beating your wife when you’re not even married: it’s a nonsense question, predestined to fail. And if you take nonsense questions seriously, you’re bound to get nonsense answers.

Rabbi Mark Kinzer addressed this issue in his groundbreaking (and controversial) essay “Final Destinies”:

… while [Paul’s] faith involves belief in a set of key truths, it is far more than the intellectual affirmation of a set of propositions. Romans 4 presents Abraham as the model of faith, and his belief in God’s promise of a son took the form of heroic trust over many years (4:19-21). His faith (pistis) was thus expressed as faithfulness (another meaning of pistis), and could also be characterized as obedience (Romans 1:5; 16:26).

So if one side of the coin is God’s covenant with humanity, our faith is the other side. Or in the words of Karl Barth, “God actualises His covenant with man by giving him commands, and man experiences this actualisation by the acceptance of these commands” (Church Dogmatics: The Doctrine of God, p. 679).

If this life matters—and I think it does—then surely it behooves us to pay attention to the “more important matters of the law–justice, mercy and faithfulness” (Matthew 23:23).

-TimK

It is all about faith.