The last clear memory I have of my school-year jobs was the VP yelling at my manager, red-faced, outside his office, right out in the middle of the hallway.

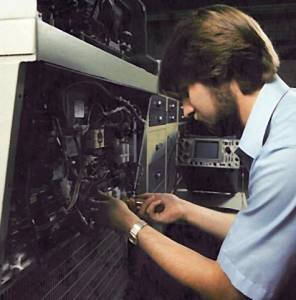

The job, at this now-defunct manufacturer of centrifuges, for me started as a co-op job in college, while I was studying electrical engineering. They hired me at a song and dance as a lab technician, to assist in the electronics lab, producing wire-wrap prototypes, helping the electrical engineers, and all-around learning about electrical engineering in the real world. This is where I met my friend Tom, who had also been working a co-op job, and was continuing to work there part-time while he took classes.

A couple interesting facts about this company: most of the engineers were mechanical engineers, not electrical or software types—that was the company’s core engineering competency; and every engineer had an office with a door. (And if you’ve ever worked in a modern engineering company—or if you’ve ever seen Dilbert—you’ll know how oddball that is.) Even I, during the time I was filling in as software engineer, I too had an office with a door.

So this company didn’t have the cubicle problem. But that’s okay, because it had every other problem.

Tom had been picking up the EE slack by designing an upgrade to one of their products—definitely not a lab-tech job. Soon after, I fell into that role as well. I worked for the company for several years. At the time, I didn’t realize how much grief I must have given my manager over those years, and if he happens to be reading this account, I retroactively apologize. But I see I also did an amount of good work, and learned more there than I had in college.

At one point, I researched, designed, and prototyped a computer-controlled driver for a three-phase induction motor. After that project was scrapped, I prepared detailed research for a new model of microcontroller that management was considering for new designs, to replace the way-too-expensive part they had been using in every single dang-blasted design theretofore. And then after the company software engineer moved on—yes, that’s “software engineer,” singular—I moved into his role… still as a lab technician.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I’m sure my boss caught a lot of grief, not only from me, but also just because he was in charge of our tiny hardware-engineering department. In the few years I was there, the department experienced almost 100% turnover. That is, except for the manager, every single staff member who was working there when I started had left by the time I stopped. (And the manager himself left soon afterward.)

I bear no ill will toward them neither for giving me an opportunity to stretch my skills nor for taking advantage of that opportunity. What I did hate was that they never invited me to the staff meetings. Tom, too. As I recall, we were at one point responsible for both hardware and software development—because both electrical engineers had quit along with the software engineer. We were making all the decisions regarding product design and function, but we were prohibited from attending the project staff meetings, because we were only co-op students. Ha! Instead, we had our own meeting and mocked them for being so petty and stupid.

With the new microcontroller, I was able to increase the accuracy of one model centrifuge by an order of magnitude. As I remember the story, when marketing found out, they were, like, “How long were you planning on keeping this a secret!?” We were not trying to hide it. However, we were not invited to the staff meetings; therefore, no one ever found out what we were up to. Oy vey.

(I don’t actually think that accuracy increase was all that important. It was kewl, but didn’t seem to have any marketing impact in the industry.)

Shortly thereafter, the company was sold, and the new VP in charge of our division told us that he would much rather see a sin of commission rather than a sin of omission, that if we tried and failed, he could forgive that, but if we did not even try at all, that would be unforgivable.

I was still young and naive, and I believed him and that he was reasonable. I didn’t realize how much corporate executives love to believe their own babble, while behaving in a contradictory manner. Now, I don’t know to what extent that was the case here, but one experience threw me for a loop and left me with the lesson: how shallow are nice-sounding words if not backed by professional follow-through. Talk is cheap; if you want to know what a man truly believes, look at what he does, not what he says.

The VP stood tall, head and shoulders above any of us, with a crazy mane of curly, black hair on top of his head. Today, the memory reminds me a bit of Michael Richards or Vincent Schiavelli.

I was walking from the back of the building, from the manufacturing area, through the mechanical lab, around a bend in the hallway, at a 4-way intersection, toward the electronics lab. As I rounded the corner, I heard someone shouting. I turned to see the VP standing face-to-face with my manager, in the public hallway just outside my manager’s office, literally yelling at him, shouting and waving his arms, towering over my poor manager as he stared up red-faced.

I didn’t know what to think of it at the time, as I was still young, but now I remember it as incredibly unprofessional and not the kind of message a boss ever wants to send to his employees.

To this day, I don’t know what the row was about, nor do I care. Whether or not my manager deserved to be chewed out. Whatever. How constructive is to yell at a subordinate in full sight of the entire company?

I like to imagine that moment as the point my manager decided to start looking for a better job.

-TimK

I want to quote you in my next blog thought. thanx.